How DNA Packaging Controls the “Genome’s Guardian”

Ever tried fitting two meters of DNA into a cell nucleus smaller than a speck of dust? Chromatin engineers do it daily. And yes, their storage solutions put even your kitchen’s Tupperware drawer to shame.

But how does p53 access its DNA targets, given our genetic material is tightly wrapped around histone proteins into structures called nucleosomes? Recent research reveals that DNA packaging actively determines which cofactors can team up with p53—adding a fresh layer of control over this pivotal protein’s activity (ecancer news, FMI news, EPFL news).

The Chromatin Challenge

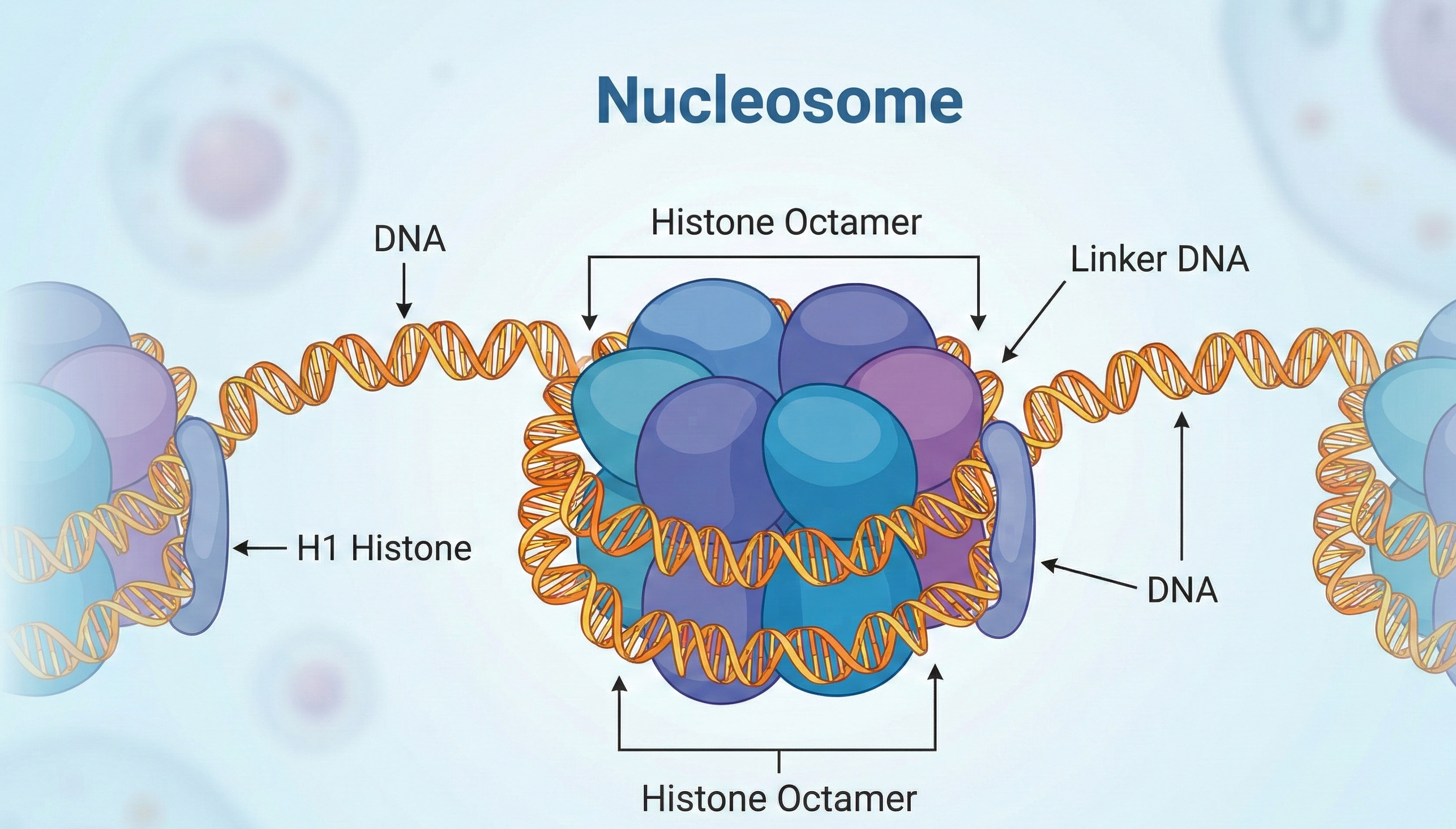

Each human cell nucleus stores about 2 meters of DNA, but you’d be forgiven for misplacing your copy; it’s all coiled up, thanks to histone spools. These nucleosomes keep DNA safe but also hide vital stretches from regulatory proteins, like p53, whose job is to patrol for genome damage and keep cell growth in check.

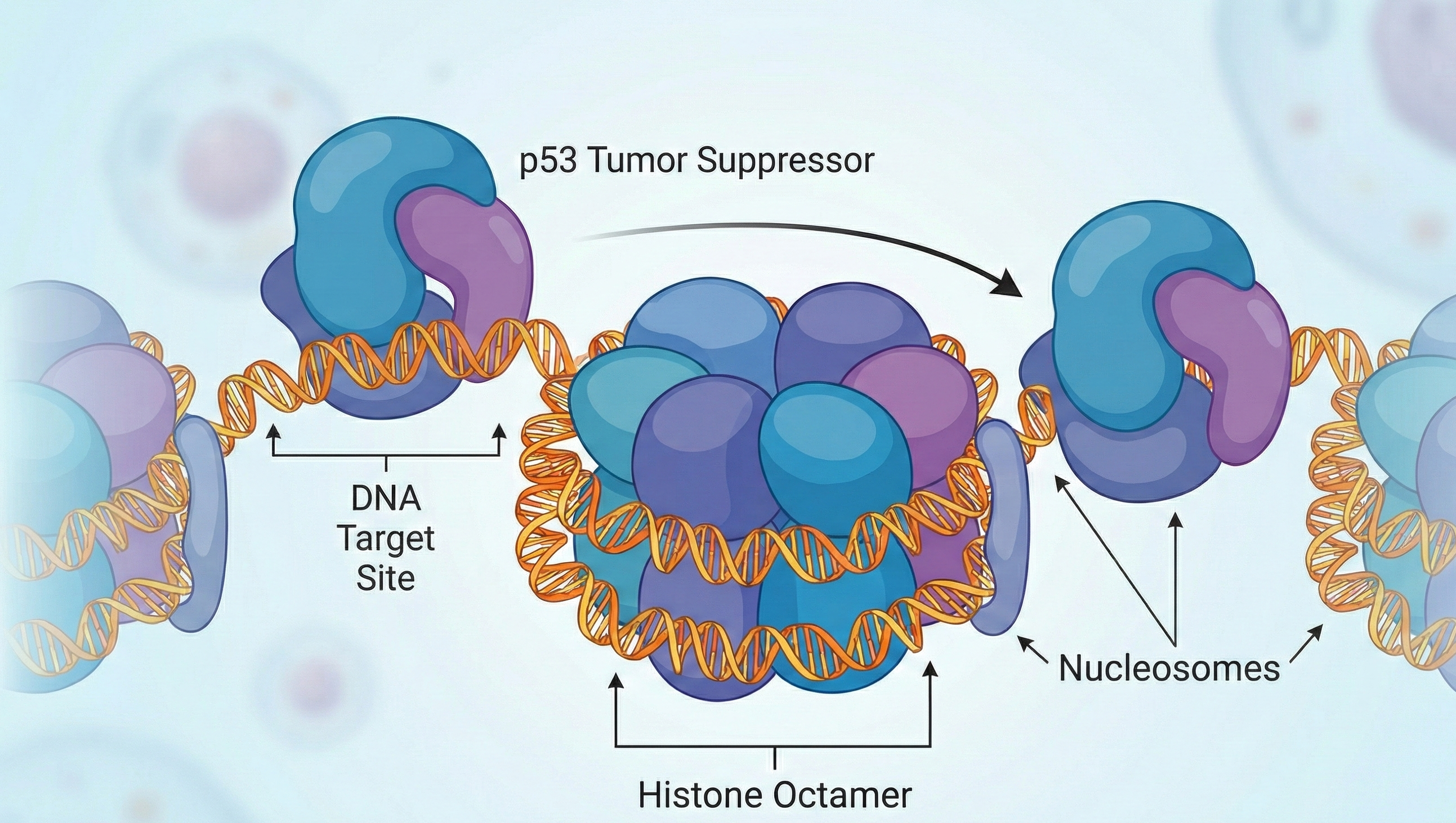

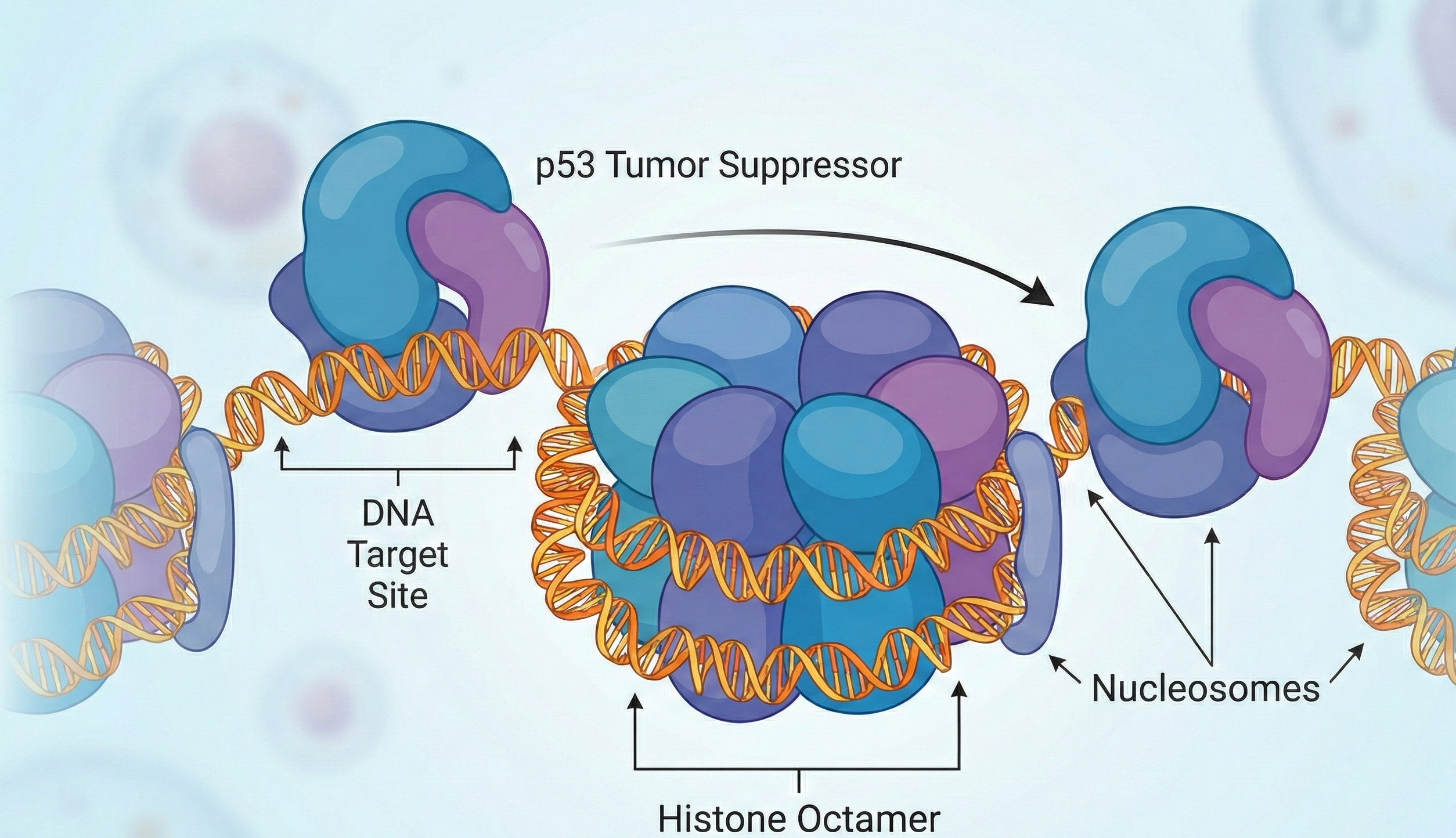

As it turns out, most of the DNA sequences targeted by p53 are buried deep within nucleosomes. Yet, p53 can still access its targets—especially those near the edges, where DNA enters or exits the spool, presumably dodging the bouncers at the nucleosomal club door.

| p53's Challenge | DNA Packaging Role | Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Find & activate target genes to halt cancer |

Nucleosomes can block or expose p53 binding sites; p53 more easily binds DNA at nucleosome edges |

Manipulating chromatin state could restore p53 function in cancer therapy |

A New Gatekeeping Mechanism

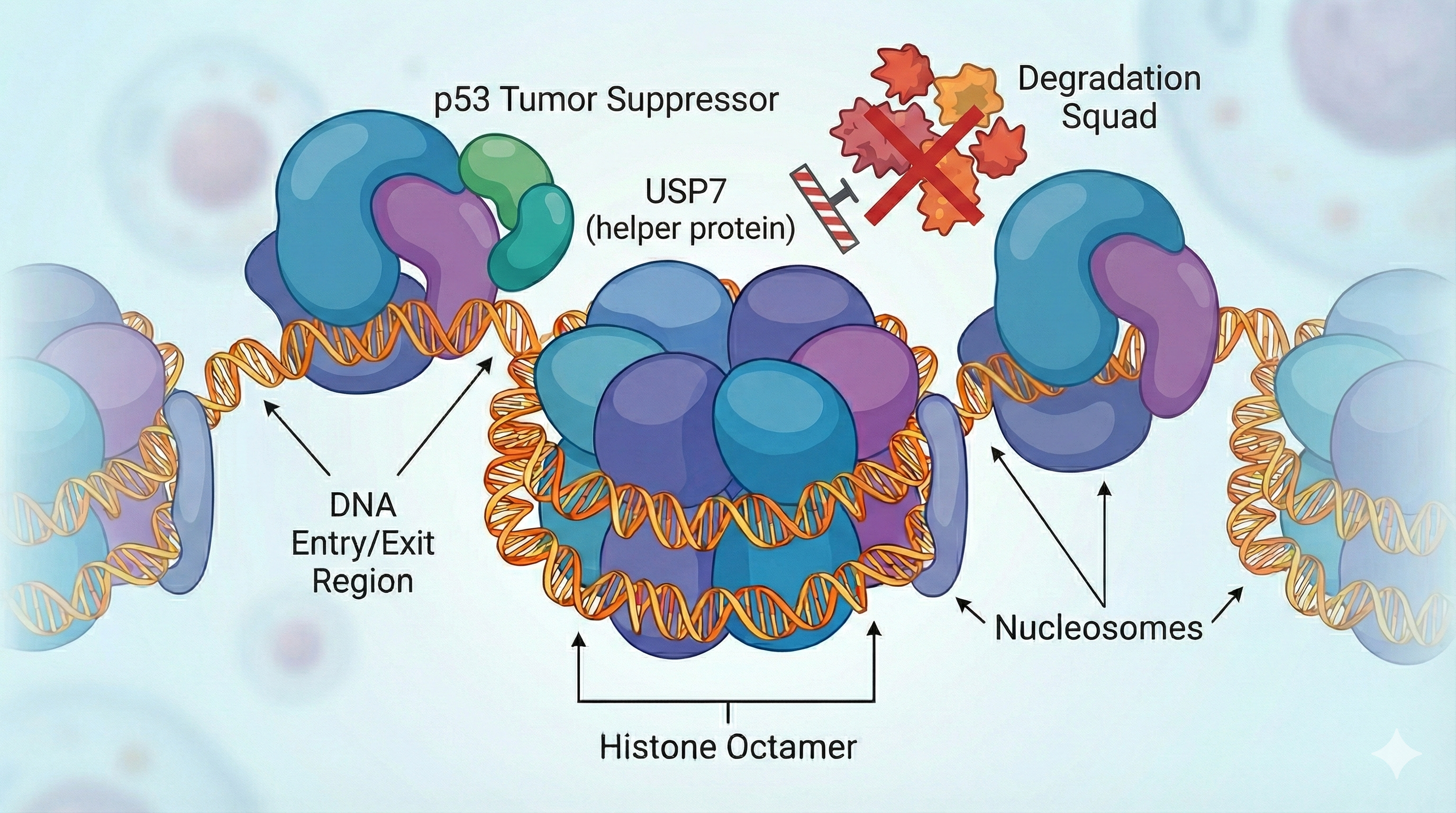

Recent research led by Nicolas Thomä (EPFL) used cryo-EM, biochemical assays, and genome-wide mapping to show that nucleosomes act as gatekeepers—controlling which proteins can interact with p53. When p53 is bound to nucleosomal DNA, key “helper” proteins like USP7 can still reach and stabilize p53, but others, such as the viral E6-E6AP complex (which degrades p53), are kept out in the cold (ecancer, FMI news).

This means chromatin architecture doesn’t just store DNA – it literally determines which protein allies (or foes) can access p53, modulating the genome’s guardianship. Forget passwords – this is the original multi-factor authentication.

Why Does This Matter?

- p53 is commonly inactivated in cancer, letting cells run wild. Boosting its DNA access—by loosening chromatin structure—could restore its tumor-suppressing powers.

- Therapeutic angle: Drugs that tweak nucleosome positioning or histone modifications might “unlock” p53’s full potential—opening tightly packed DNA to surveillance

- Basic biology bonus: This reveals a new level of epigenetic control over cell fate and genome stability.

Take-Home Message

If you ever feel locked out of your own house, spare a thought for poor p53 trying to check on your DNA while nucleosomes keep slamming the door. At least you don’t have to negotiate with histone-modifying enzymes.

For clinical development, this highlights the fast-evolving landscape at the intersection of epigenetics, cancer biology and targeted therapeutics—where knowing how DNA is packed is just as important as knowing what it encodes.

Compiled August 7, 2025, with the latest research from Molecular Cell, EPFL, FMI, and ecancer.

For further technical deep-dives, contact your neighborhood chromatin biologist—ideally before the DNA repair team arrives.